Originally from The Intercept

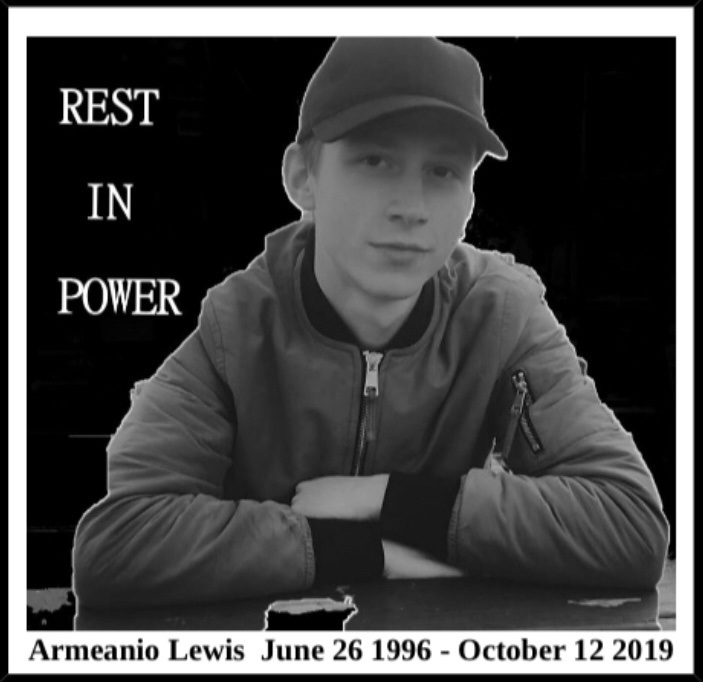

See also: Armeanio lives! Citywide Attack in Memory of Sean Kealiher

On the day of President Joe Biden’s inauguration, dozens of protesters in Portland, Oregon, marched to the state Democratic Party’s headquarters, carrying signs against police and the incoming administration. “We don’t want Biden, we want revenge,” one of them read, “for police murders, imperialist wars, and fascist massacres.” A few protesters, dressed all in black and with their faces covered, smashed windows, scrawled graffiti, and set a trash canister on fire.

It was a familiar scene in Portland, which was gripped by more than four months of almost-uninterrupted protests last summer following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Local police, under the leadership of Portland’s Democratic mayor, had met those protests with tear gas and violence. But as the city became the epicenter of a nationwide protest movement of historic proportions, it also became a symbol of former President Donald Trump’s battle against antifa, the far-left, radical ideology those black-clad protesters had come to represent. At the height of the protests, Trump sent dozens of federal troops to Portland, where they doubled down on local police’s repression, at one point disappearing demonstrators into unmarked vans. The administration also devoted significant resources to a failed attempt to build its case against antifa, short for anti-fascists, which officials tried to designate as a terrorist organization. As part of that effort, they reassigned scores of prosecutors and FBI agents who had been focused on other threats, like the one posed by far-right extremists — an intelligence failure that was put on stark display when supporters of the president staged an assault on the U.S. Capitol days before he left office.

With Trump now gone, the Inauguration Day protest in Portland was a warning that a change in administration would have little effect on the city’s streets. Portland has a long history of anti-fascist activism, deeply intertwined with its history of white supremacist violence. And while it was largely Trump who elevated antifa to a household name, generations of Portland anti-fascists have for decades opposed far-right, racist extremists as well as police.

Few anti-fascists were as influential on Portland’s recent protest scene as Sean Kealiher, a young anarchist who became a fixture on the city’s streets after he joined an Occupy Portland encampment in 2011, when he was 15. Over the years, Kealiher moved in and out of many of the city’s leftist groups, as he kept reelaborating his belief system to be more radical than most others’ in his circle. “Once other people caught up to him, he would look for ways to go even further left,” one of his friends told me. Kealiher was always arguing with someone and would regularly storm out of meetings with other activists, accusing everyone of being a bunch of liberals. But he would always turn up at the next protest. “If something was going down, he would be there,” his mother, Laura Kealiher, told me.

Sean Kealiher, center, attends a “Solidarity with Charlottesville” rally in Portland, Ore., on Aug. 14, 2017.

He trained fellow protesters on how to protect themselves from police violence and far-right incursions and championed strategies like “de-arrests.” And he was an early proponent of black bloc, a tactic that includes the face coverings that have become an emblem of antifa. He would always make sure everyone’s hair and eyebrows were carefully tucked under their masks and lecture them about good security culture. “He was incredibly influential, potentially more so than almost anybody in our protest scene,” said Gregory McKelvey, a well-known Black Lives Matter activist who became friends with Kealiher despite their political differences.

Kealiher, whom most people knew by the pseudonym Armeanio Lewis, rarely missed a protest, and he would have been front and center last summer when the insurrectionary activism he had long advocated for became a staple on Portland streets. “He sure would’ve been excited to see the justice center and the police union building on fire,” a group of his friends wrote to me, referring to city buildings protesters set ablaze during the protests. “It would have been the absolute time of [his] life,” another friend said. Cynical as he was about electoral politics, Kealiher would have certainly been there on the day of Biden’s inauguration. But he wasn’t there then, or last summer: He was killed in October 2019, at 23, in front of the Democratic Party building that protesters vandalized on Inauguration Day.

Few details of Kealiher’s death have been publicly revealed. What is known is that he was walking with two friends outside Cider Riot, a now-shuttered pub that was popular among anti-fascists and had been the site of confrontations with far-right groups earlier that year. An argument erupted between Kealiher and his friends and another group, who got into an SUV and drove away, then pulled around and accelerated, slamming into Kealiher and crashing into the building. When the driver tried to reverse, one of Kealiher’s friends pulled out a licensed handgun and fired at the car; he believed the driver was about to plow over Kealiher again, according to an account given by the friend’s attorneys shortly after the incident. The people in the car got out and ran off, leaving the vehicle behind and Kealiher bleeding on the sidewalk.

Death of an Anti-Fascist

Kealiher’s death shocked Portland’s activist community. Because it happened so close to Cider Riot, many on the left immediately feared that the attack had been politically motivated. “The first thing we heard is that he had been killed right outside the bar that we all go to,” one of his friends told me, noting that threats and attacks from far-right individuals were not uncommon. “People were kind of worried at first for their own safety, if this was something that was going to start happening.”

The death was ruled a homicide, but no arrests were ever made and no persons of interest named. In the absence of official updates, speculation about what happened swirled for weeks. None of the people involved spoke publicly about it, and most of Kealiher’s friends honored his mother’s request not to speak with journalists. Nearly all those who spoke with me did so on the condition of anonymity. “In the beginning, we really didn’t know who did what, was it political or not, and I didn’t want to be part of that, to start some type of war,” Laura Kealiher told me. “I just wanted people to be quiet and let the police do their job.”

But more than a year after her son’s death, Kealiher regrets trusting police, whom she now believes had no interest in solving the murder of an activist who made no secret of his contempt for them. She and others have come to the conclusion, based on their own investigations, that Kealiher’s killing was not targeted, but rather the result of an argument that had nothing to do with his politics or those of his killer. Still, the killing, and the fact that it remains unsolved, has left a deep wound and seething anger in a city that has for decades been a battleground for far-right violence and has seen that violence resurface in recent years. “Even though it likely wasn’t distinctly political, it felt like it was, given the period,” a friend of Kealiher said. “Even the fact that we would assume originally that it was some kind of targeted killing I think echoes that feeling. It comes amidst a lot of violence and a lot of attacks, a lot of people looking over their shoulder.”

The apparent lack of a robust investigation also underscores the political bias of which many in Portland have long accused police, and those in Kealiher’s circle saw his unsolved murder as further confirmation of the police’s double standards and antagonism toward the left. “Had it been someone else’s murder, it would have been solved,” said McKelvey. “I wouldn’t be surprised if police officers were not very interested in investigating this murder.”

Kealiher’s mother and friends believe that police had plenty of evidence, including security camera footage and the suspect’s car, which she and others quickly connected to a registered owner and his relatives. “It really does appear that the police are just refusing to do anything with this case,” said a friend. “They know who owns the car, I think everybody knows who owns the car. … You’d think they’d just go arrest the guy, but they haven’t. And they won’t, because Sean was somebody they hated.”

Brent Weisberg, a spokesperson for the Multnomah County District Attorney’s office, wrote in a statement to The Intercept that “this is still an active investigation with law enforcement regularly discussing ways to advance the case to a prosecution.” Weisberg added that the office met with Kealiher’s family several times and will continue to update them as the investigation proceeds, “while always being mindful to preserve the integrity of the criminal investigation. We continue to ask that anyone with information on this case contact Crime Stoppers of Oregon.” The Portland Police Bureau did not respond to a request for comment.

Kealiher’s case was reminiscent of earlier incidents in which Portland police did little to investigate violent attacks against anti-fascists, which police often dismissed as gang-related violence, treating victims as suspects. Some pointed to the 2010 shooting of Luke Querner, an activist who was left paralyzed from the waist down in an attack that fellow anti-fascists connected to local neo-Nazis before police did. And a friend of Kealiher who has been around Portland’s activist spaces for decades noted that the apparent reluctance of police to intervene reminded him of their hands-off approach to violence between racist skinheads and anti-racist activists, which was frequent in the city during the 1980s and ’90s. “There is a feeling in Portland, Oregon, that if an anti-fascist is killed, or somebody tries to kill them, the cops aren’t going to do anything about it,” said the friend, who recalled police twice refusing to investigate shots fired at homes he shared with other activists in the ’90s. “I think the lack of a police investigation was politically motivated.”

A Washington state trooper works the scene at Tanglewilde Terrace, the apartment complex where law enforcement officers shot and killed Michael Reinoehl, in Lacey, Wash., on Sept. 3, 2020. Reinoehl was being investigated for his role in a fatal shooting at a pro-Trump rally in Portland, Ore.

Several people also pointed to the disparities in police’s handling of Kealiher’s murder and their response after a self-declared anti-fascist shot and killed Aaron Danielson, a supporter of the far-right group Patriot Prayer, during last summer’s protests. The man who killed Danielson, Michael Reinoehl, was himself shot dead days later by federal law enforcement officers — a killing Trump hailed as “retribution” and others denounced as an extrajudicial execution. “The shooting of a prominent right winger this summer in Portland resulted in the feds ambushing the shooter and killing him in an apartment complex parking lot. Anybody can do that math,” the group of friends wrote to me. “The police executed that guy,” said another, referring to Reinoehl. “They found him really fast and made a point that they’re not even letting him get a trial. But in Sean’s case, they can’t even make an arrest.”

The stalled investigation also highlights the distrust of police that runs deep in many communities, hindering their ability to investigate crimes. That’s a problem police have largely brought on themselves, critics say, as they have aggressively targeted everything from homelessness to protest while failing to address real safety concerns in those communities. Kealiher himself hated the police. “It would be nice if we could find a stronger word,” his friends wrote, “but no word exists that could sum up the contempt he had for the army which occupies our neighborhoods.” After his death, social media trolls criticized the friends who were with him for driving him to the hospital without calling police or an ambulance. One of them, who did not identify himself in his emails to me, said that he and the other friend “grabbed Sean out from under the car” that struck him and rushed him to the hospital, performing CPR in the backseat as they drove there. Kealiher wasn’t conscious, he added. An attorney representing one of Kealiher’s friends declined to comment; the second friend was never publicly identified.

Laura Kealiher insists that she does not blame her son’s friends for their choices that night or for their refusal to collaborate with police. “They need to do what’s right for them,” she told me. “And honestly, most likely, if there is an arrest made, they probably would not testify because of their beliefs.” Those beliefs, a fundamental rejection of police and the justice system, were essential to the way Kealiher himself saw the world, leaving his mother and friends with few answers about what justice for his death should look like. “The problem is that people don’t trust the police, and that’s not people’s fault, that’s the police’s fault,” said McKelvey. “It sucks to be in a situation where maybe he would have lived if people could trust calling 911. … But I guarantee you that he would not have wanted people to call 911.”

Kealiher’s mother had raised him to believe that police are “our friends,” she told me, but she had grown disillusioned with them as he began to get arrested at protests when he was still a minor. Once, when he was 15, an officer punched him in the face, she said. Another time, she was watching the news at work when she saw two officers tackling him to the ground. At the hospital the night he was killed, Kealiher was taken aback when police seemed more interested in her son’s friends than in his killer. “They didn’t want to know what had happened,” she said. “They only cared about who he was associated with.”

Still, Kealiher did speak with the detective in charge of the investigation, Scott Broughton, and with several people at the district attorney’s office. At their first meeting last February, a prosecutor told her that charges were forthcoming and to prepare for a grand jury process and media inquiries, she said. A victim’s advocate offered her counseling, even telling her that she was going to need it as the case was bound to get a lot of attention. “And then I didn’t hear anything,” Kealiher told me. In the following months, as the pandemic ground much of the country to a halt, she kept trying to get ahold of someone from the DA’s office, with no success. She called Broughton repeatedly, she said, never getting a call back. Broughton did not respond to requests for comment via email and voicemail message.

“They didn’t want to know what had happened. They only cared about who he was associated with.”

Last May, Portland voters elected a new district attorney, who took office in August when his predecessor retired ahead of schedule amid the protests. The prosecutor who had been working on Kealiher’s case left the office in June, and his mother only heard from the new one assigned to it after posting on social media in an effort to bring attention to her son’s unsolved murder. At one point, she even reached out to the office of Sen. Jeff Merkley, whose son had played soccer with Kealiher as a child. Sara Hottman, a spokesperson for Merkley, wrote in an email to The Intercept that his office was unable to provide assistance because the case is under the jurisdiction of local police and the county district attorney. “Our hearts are with the family and we hope that justice will be well-served by the ongoing investigation,” Hottman wrote.

When Kealiher finally met the new prosecutor on a video call last August, he told her that police were “not even near an arrest,” she said, and that the prior prosecutor should have never said that was the case. He also tried to reassure her by telling her that there’s no statute of limitations on homicide, she said, which infuriated her. She hasn’t received an update since then.

As the months went by, Kealiher grew frustrated with what she saw as police’s inaction and suspicious that they were purposefully holding back the investigation. “I think they are actually hoping that somebody on the left will do street justice,” she told me. “They know that the left knows who did it, and they are hoping to get one of them to do something so they can target them, because they’d rather arrest somebody on the left.”

On the first anniversary of Kealiher’s death, police issued a Crime Stoppers alert, offering $2,500 for any information relating to the case, which friends took as an admission that they had made no substantial progress. Then last December, tired of waiting, Laura Kealiher wrote a private Facebook message to the man she believes killed her son. When he didn’t respond, she identified him in a TikTok video, in a desperate effort to force answers about her son’s death. The video was quickly reported and taken down, though another video in which she named the man remains online. (The Intercept has been unable to verify her account.) Kealiher faced much criticism over it, including from her son’s friends. “I really caution people running around posting people’s faces and names,” one of them told me. But she finally got a call back from police. When she spoke with Broughton, she said he yelled at her and demanded to know how she had learned the identities of the people in the car. She refused to answer and stopped taking his calls. She is no longer collaborating with the investigation, she said, because she does not believe police have any intention of solving the murder of an anti-fascist. “He wasn’t killed because of his activism,” she told me. “But he is not getting justice because of it.”

American Antifa

Kealiher’s coming-of-age as an anti-fascist coincided with the normalization of far-right ideology and escalation in far-right violence that defined the Trump presidency. Few places were as central to that resurgence as Oregon, which was founded as a whites-only state and has remained a hotbed for white supremacists throughout its history. Largely in response to that legacy, Oregon has also long been a key hub for anti-fascist activism, a movement that developed out of decades-old anti-racist organizing. Anti-racism and anti-fascism have always been deeply intertwined in the United States, and the American anti-fascist tradition can be traced back to long before fascism got its name in early 20th-century Italy. “The spirit of anti-fascism as an opposition to an ideology that believes in an inherent inequality between people and enforces that inequality through violence, I trace that all the way back to — in the U.S. — the history of the abolitionist movement,” Stanislav Vysotsky, a sociologist and author of a book about American anti-fascism, told me in an interview. “There’s this history in the United States of people opposing that kind of ideology, even before it had a name.”

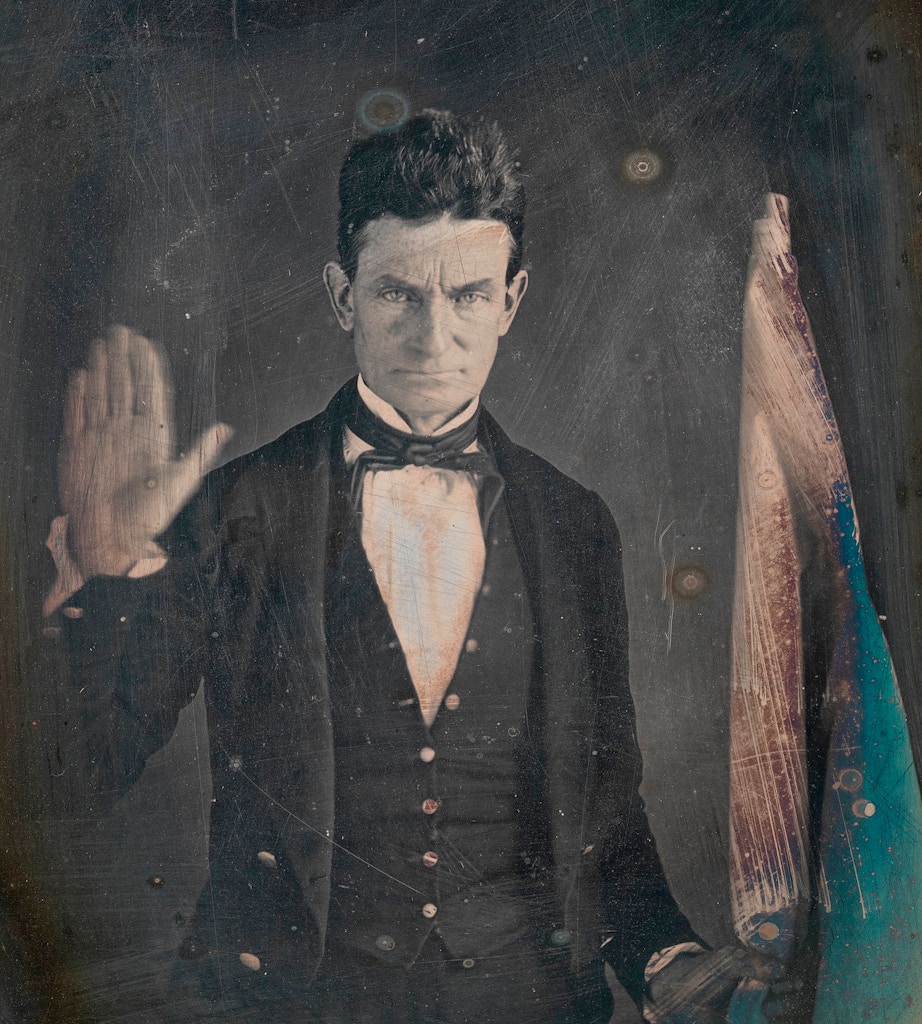

Daguerreotype portrait of abolitionist John Brown circa 1846.

What many came to know as “antifa” largely evolved out of anti-racist groups like the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee, named after the 19th-century abolitionist, and Anti-Racist Action, a nationwide network that at its peak counted more than 120 chapters and thousands of members, according to Vysotsky. These groups, which in turn drew inspiration from the more militant elements of the civil rights movement, like the Black Panthers, focused on opposing traditional white supremacist organizations, like the Ku Klux Klan, and emerging ones, like the National Alliance and the World Church of the Creator, as well as a host of racist skinheads and neo-Nazi street gangs that proliferated in cities like Portland.Throughout the 1980s, violence by such groups was pervasive in Oregon, reaching its peak in the 1988 murder of Mulugeta Seraw, an Ethiopian student who was beaten to death with a baseball bat by three members of the neo-Nazi White Aryan Resistance. (One of them, Kyle Brewster, recently resurfaced at a series of pro-Trump rallies in Portland.) Those years were defining for many who grew up to embrace anti-fascist politics in Portland. “That was a really key point of left-wing political consciousness,” a friend of Kealiher told me. Anti-racists, including groups like the Baldies, which originated in Minneapolis, and Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice, or SHARPs, regularly clashed with racist gangs, although anti-racist activism largely consisted of publicly outing individuals affiliated with racist groups, a key component of today’s anti-fascism.

While they conceived of their work as anti-racist, these groups were less focused on tackling racism as a systemic, institutionalized issue than they were on exposing and battling racist extremists. But the line between institutional and extremist racism was sometimes blurred, as in the case of Portland police officer Mark Kruger, a Nazi sympathizer who remained on the force for years after being exposed and whom Portland anti-fascists often refer to when explaining their views of police. Since the 1990s, anti-racist groups have expanded their focus to include “copwatching,” a shift that brought them closer to the racial justice movement and more directly defined their position in relation to state violence. The first to adopt the “anti-fascist” name in the U.S. were the Northeast Anti-Fascists, a group founded in Boston in 2002. Then in 2007, Portland anti-fascists formed Rose City Antifa to coordinate opposition to a large gathering of neo-Nazis in the city. They were the first in the U.S. to take on the abbreviated antifa moniker.

While anti-fascists had been active for years before Trump’s political ascendance, it was in the Trump years that most Americans first heard the term, under Trump that anti-fascism as an ideology grew in influence, and through Trump that “antifa” became public enemy No. 1 for far-right activists and right-wing media and a primary target of law enforcement agencies and conservative lawmakers. That development can be traced in parallel with a shift happening on the far right, which in the years leading up to Trump’s presidency became more technologically and media savvy as well as increasingly mobilized and confrontational. Before Trump, there had been attempts by far-right groups to move from the fringes into mainstream conservative politics, but for the most part, the Republican Party had been careful not to openly associate with their explicit racism. Then came the 2016 election. “Trump comes in, he runs for office on this platform that from day one is white supremacist, white nationalist talking,” said Vysotsky. “He is talking like the fascist movement in the United States, which had been operating underground.”

Top: Anti-fascist activists counterprotest at a Patriot Prayer rally in downtown Portland, Ore., on Aug. 4, 2018. Bottom: Members of Patriot Prayer are seen during an “alt-right” rally at Tom McCall Waterfront Park in Portland, Ore., on Aug. 4, 2018.

The impact was immediate, as reenergized extremists emerged from the shadows, elevating Trump to an avatar for their movement. At rallies, support for Trump and for far-right, racist ideology became indistinguishable while the president repeatedly encouraged his most extremist and violent supporters. Hate crimes and far-right violence spiked across the country, with perpetrators often citing the president as justification for their acts. In Portland, in May 2017, Jeremy Christian, a white supremacist, stabbed and killed two men and injured a third who had intervened when Christian yelled racist and anti-Muslim slurs at two Black teenage girls on a city train. But even as far-right extremists grew emboldened and more violent under Trump’s watch — culminating in the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where neo-Nazi James Alex Fields Jr. drove a car into a crowd, killing Heather Heyer — his administration dismissed the threat posed by the far right and searched for enemies elsewhere.

A week after Charlottesville, the FBI distributed an intelligence memo to thousands of law enforcement agencies, warning of the rise of an ideology it called “Black Identity Extremism.” And for the last several years, the Trump administration tried to suppress reports of growing far-right violence and even the use of the term “domestic terrorism” in reference to it, all while pressuring officials to build baseless conspiracy cases against left-wing activists and trying to designate antifa as a terrorist group. Even in the aftermath of the assault on the Capitol, a number of far-right figures promoted the lie that antifa, rather than the president’s extremist supporters, was responsible.

Antifa proved the perfect enemy for Trump, feeding into fears born of two decades of war-on-terror rhetoric. Some anti-fascists espoused militant tactics like smashing windows and setting fires and sometimes engaged in physical violence with opposing groups and police. But while their rhetoric was regularly more violent than their actions, and even though anti-fascist violence never escalated to anywhere near the level of far-right violence — Danielson’s killing is the only one attributed to an anti-fascist to date — the black-clad rioters captured the imagination of their opponents. “The right gets this enemy, this villain, in antifa,” said Vysotsky. “This creates a perfect monster. … Here is this left, out of control, that’s coming for you, and it’s violent and dangerous and foreign, and they’re wearing all black, and they’re really scary.”

Then last summer, tens of thousands of people took to streets across the country to protest police violence, the vast majority of them peacefully. Anti-fascists became a regular presence at protests, where they sometimes marched in solidarity with Black Lives Matter activists and at other times set fires or vandalized buildings. As the Trump administration ramped up its rhetoric against antifa, former Attorney General William Barr declared Portland, Seattle, and New York City “anarchist jurisdictions” and threatened to withhold federal funding. But officials also redirected significant resources to Portland in an effort to bolster the president’s war against antifa, a deployment that put a drain on the Justice Department at a time when it had about 1,000 domestic terrorism investigations open, most of them of white supremacists. The move not only served as a distraction from the threat posed by far-right extremists, but also had the effect of validating their ideology, presenting violent groups like the Proud Boys, who were instrumental in the assault on the Capitol and had turned Portland into a practice ground, or Patriot Prayer, based in a suburb of the city, as part of a united front against the radical left.

Kealiher had predicted that shift. “Fascism now is a political point that can be debated,” he explained in a 2018 radio interview with McKelvey. “They see an opening, a social rupture so to speak, as anarchists call it, where they can intervene with their politics and recruit.” Kealiher saw “antifa” as a label outsiders used to sensationalize elements of what to anti-fascists is a more complex political practice. “Antifa is the media side, and the spectacle side, of what we consider anti-fascist methodology,” he said in the interview. “To be an anti-fascist is simply to make an ideological disagreement with fascism. To be antifa is to get roped into the media blitz and the media stories and let them control the narrative about our politics.” Then, with his usual levity, he explained anti-fascism more simply. “It is 99 percent boredom and 1 percent of fun, flashy, fight scenes,” he said. “When people think anti-fascists, they think, ‘Oh here’s the big, scary guys, and they are [in] all black.’ When actually, it’s me, in my underwear, at 3 in the morning, going through the white pages, court records, voting records, and trying to find addresses.”

The Democratic Party of Oregon headquarters, seen on Jan. 29, 2021, was the site of an anti-facist and anti-police protest on Inauguration Day, when protesters broke windows and set a fire in a nearby dumpster. The street in front of the headquarters is where Sean Kealiher, 23, an anti-facist activist, was killed after leaving a nearby bar in 2019.

Why Break Windows

There is an enormous divide between the way antifa is understood by its fiercest critics and the way anti-fascists conceive of their politics. “Anti-fascists are not the threat that is constructed in right-wing media,” said Vysotsky. “Anti-fascism is only really a threat to you if you are a fascist.” Kealiher was a “proud anti-fascist,” his mother said, but he was wary of labels that he saw as easily coopted, including that one. Instead, his values and personal ethics boiled down to a simple position: “It was always the correct path to fight back against oppressive groups,” a friend explained. Or, as Kealiher himself put it in the radio interview, “There’s a myriad of things, but no one political ideology is at fault — except fascism.”

After Kealiher’s death, the right-wing Portland writer Andy Ngo published an article resurfacing writings Kealiher had posted online, including one in which he described violent action as “the most beautiful moment an anarchist can undertake.” In that 2017 essay, a bombastic manifesto titled “Why Break Windows,” Kealiher wrote about “feeling the adrenaline of rushing to a window with a rock in hand, or the moments before striking a cop with your fist. Planting the bomb, pulling the trigger, shouting FUCK THE POLICE.” He criticized what he saw as “liberal” nonviolent resistance, but also appeared clear-eyed about the limits of violent action. “It won’t change the world, but it will change your night,” he wrote. “Nobody is going to argue that smashing a window will incite a mass and global revolution where workers worldwide seize the means of production and finally abolish the state, absolutely nobody argues that, because that is not the point of breaking a window.”

Kealiher’s argument was consistent with other anarchists’ belief in the power of insurrectionist action in the moment, for its own sake. “The goal isn’t always what’s on the other side of the fight, the goal is the fight itself,” a friend explained. But the friend also noted that Kealiher liked to play the part of the hardcore revolutionary: He “told stories a little bit,” the friend said, had a penchant for “shit-talking.” He warned against interpreting his writings too literally. “For a young person that likes to talk tough sometimes and is on an ideological train all the time,” he asked, “can you really say that when they’re talking about these different revolutionary things that they mean it in a really profound way or sincere way?”

“He was a very positive person despite all the rage he felt at the world around him. He was strangely capable of bringing people together, for somebody who also seemed to be able to get under people’s skin.”

Fellow protesters put up with Kealiher’s propensity for jargon and ideological posturing because he also put in real work — he wouldn’t just “walk around from an armchair,” the friend added. He would be there to move barricades and distribute food, occupy homes slated for eviction, and wait for hours in the cold for people to be released from jail. He never had money but would do things like offer a place to stay to people he had never met in person. And for someone who held a largely pessimistic view of the world — in one of his essays he argued that “it doesn’t get better and that’s okay” — he had a surprisingly upbeat, joyful personality and unwavering love for those he called his comrades. “He was a very positive person despite all the rage he felt at the world around him,” his friends wrote. “He was strangely capable of bringing people together, for somebody who also seemed to be able to get under people’s skin.”

Kealiher was perennially disillusioned with what he saw as the failures of the left and had no patience for the drama and infighting typical of social justice movements. But while he had a strong preference for direct, militant action, he respected the decisions of those with different tactics and never sought to change the nature of a protest he had not organized. He would work with anyone, a friend said, “as long as they’re fighting for justice.”

Anti-fascism, to Kealiher, was a pragmatic affair. It sometimes manifested in what outsiders saw as vandalism or violence but to him was the necessary response to worse violence. McKelvey, the Black Lives Matter activist, recalled a May Day protest in 2017 when police attacked a peaceful parade that included families with children. Kealiher and others dragged barricades into the road to block the officers, lighting fires to slow them down and allow people to leave. City officials and the media portrayed the episode exclusively as an example of left-wing destruction. “I remember the video being used … to show how reckless and bad these anarchists are, but he was doing that because there were families in this parade that were trying to get away,” said McKelvey. “He was not a pacifist at all, nor peaceful, but he was defense-oriented.”

With right-wing activists and police, Kealiher was confrontational and aggressive, although verbally more than physically. Officers had gotten to know him by name, and frequently called him out at protests, cursing at him just like he did at them. Once, after he was arrested for refusing to move off a street as police responded to a call, the arresting officer testified in court that Kealiher had blocked his car and called him “a fat, fucking pig.” When Kealiher’s turn on the stand came, a friend who was there recalled, “He goes up there and he says, ‘I just want to clarify, I didn’t call him a fat, fucking pig. I just called him a fucking pig.’ Because he doesn’t use ableist language.” Kealiher got a 10-day jail sentence on that occasion, an unusually severe punishment for interfering with a police officer.

Like other anti-fascists, Kealiher viewed violence as a “practical necessity” in response to far-right and police violence, his friends wrote, because “[f]ascists threatened his safety and his freedom, not just in a philosophical sense, but in the practical sense, on the streets.” Kealiher made a similar point in his radio interview: “If we’re not violent, they will be.”

Those views made many on the left uncomfortable. Once, when McKelvey was asked to line up speakers for an event, he tapped Kealiher to represent a more radical perspective. “The crowd mostly didn’t like it,” he said, recalling how he had stood uneasily by Kealiher as he spoke in his typically fiery fashion. “We’re talking to people that would go to the Women’s March one day, and then the next day, here’s Armeanio talking about punching Nazis and stuff like that, and we need to arm ourselves and fight and be anarchists.” But, McKelvey added, “it really was often the more radical factions and anarchists who would protect people at protests when shit really hit the fan.”

The question of violence has always been central to anti-fascism, although observers have sometimes collapsed anti-fascists’ destruction of property with physical violence. Anti-fascists conceive of violence as a strategy that must be restrained and framed as defensive, even when it is not obvious that it is, said Vysotsky. “The idea is you use just enough force to demobilize fascists,” he said. “That’s why anti-fascist violence is fairly limited to the kinds of scuffles you see at protests and the kinds of street fights that you might see when confronting fascists in an everyday context. But it very rarely rises to extreme forms of violence.”

Until recently, at least, anti-fascists would mostly set up human walls to encircle protesters from police or opposing groups, sometimes resulting in skirmishes, or they would show up at the site of a far-right rally to “claim the space” before others did, a Kealiher friend said. But in Portland, violent confrontations became more frequent in recent years, and protesters who last summer clashed with police night after night noted that officers took a remarkably different, hands-off approach when right-wing activists showed up, allowing opposing groups to fight each other without intervening and even telling people over loudspeakers to “self-monitor for criminal activity.”

Then on August 29, Reinoehl shot Danielson as he sprayed a can of mace during a night of clashes. While it remains an isolated incident, the killing is emblematic of the sharp rise in tensions at Portland protests and of the willingness among some on the left to engage in extreme violence. Many anti-fascists condemned both Reinoehl’s actions and those of the federal officers who then killed him. “That he responded with gunfire to pepper spray is something that none of us would have ever wanted,” said a Kealiher friend, who had not known Reinoehl. “Because if that’s an appropriate response, every clash we have had in the past five years would have ended up in gun fights.”

As far-right activists have increasingly showed up armed at protests, so have some on the left. “The idea of a violent attack, of being shot by the far right, that’s very real,” another Kealiher friend said, noting that members of Rose City Antifa have been shot at by far-right activists. Leftists didn’t use to have guns, he noted, but “unfortunately that has changed, and it’s unfortunate that that’s changed because I don’t think it’s going to de-escalate the situation.” Kealiher himself talked about being a supporter of the Second Amendment. “I like my guns,” he said in the radio interview. His friends said that they never saw him armed at a protest and that it would have been unusual for him to carry weapons in a situation where he faced significant risk of arrest. But they weren’t surprised to learn that someone Kealiher was with had a gun the night he was killed.

“When you are thinking about Portland, and you’re looking at the level of violence that has been occurring in Portland over the last five years of so, it’s safe to say that there are going to be people who are going to be concerned for their safety,” said Vysotsky. “Fascists are making explicit threats. They are armed. And their ideology tells them that they should use violent, lethal force against their enemies. It’s pretty hard not to take them seriously.”

Armeanio Lewis

Kealiher got his first exposure to militant politics by way of his proudly Irish family; a family friend, in particular, was an active supporter of the Irish Republican Army, and as a child Kealiher was fascinated with the idea that “the IRA, he felt, really fought for the people,” his mother said. He had grown up in a middle-class, mostly white neighborhood, but his life changed virtually overnight after a family dispute forced his single mother to move into a much poorer neighborhood. Kealiher had to transfer from a great public school into a struggling, more diverse one, where he got a crash course in the politics of inequality and segregation. As he began to understand his new circumstances in terms of class struggle, Kealiher was also exposed to racism for the first time. When he was 13, he was suspended from school when someone yelled a racist slur at one of his Black friends; he responded by “choking the guy out,” his mother said — an early foray into his years as an anti-racist activist.

In 2011, during a school field trip downtown, he stumbled upon an Occupy Portland encampment that had been set up in the wake of the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York. There, Kealiher found a framework to process the social injustices he had come to despise and an outlet for a growing anger his mother said she had repeatedly tried and failed to get him counseling for. He lied to her about where he was spending the night and started sleeping at the camp, where people knew him by the name “Yaka.” “When he saw Occupy, he found his voice,” his mother said. The protest scene proved exhilarating for him, but he also became enthralled with the ideologies he heard referenced there.

When he wasn’t at a protest, Kealiher was online, researching the personal information of neo-Nazis, chatting with activists in Greece, or emailing prominent leftist thinkers. He got an anarchist tattoo, and for a while he went by the name Anteo Zamboni, a tribute to a 15-year-old Italian anarchist who was lynched after shooting at Benito Mussolini’s car. By the end of his life, he had become a SHARP and was known to most in Portland as Armeanio Lewis.

A high school drop-out, he was profoundly intellectual and sharp-tongued, with an encyclopedic knowledge of early 20th-century politics and the history of the left. He would quote obscure theorists or debate the roles of Trotskyists and anarchists during the Spanish Civil War to anyone who would listen. “A lot of it went over my head,” said his mother, but she gradually came to embrace her son’s politics.

Far-right activists hated Kealiher as viscerally as he did them. He had been well known to them since at least 2016, when a video that showed him confronting a group of pro-Trump students at a Portland State University event went viral on conservative media outlets. There were more videos like it. In one, Kealiher confronts Christian, just a month before Christian killed two people on a city train. Kealiher didn’t hesitate to put himself “out there,” his mother said, and he became the target of doxing, abuse, and threats that lasted through his life. He rarely talked about it; to his friends, he seemed fearless and unfazed. “I think he also knew that anytime something bad could happen,” his mother said. “He had a big target on his head. … I would say, ‘You know they want you dead.’ And he said, ‘I know, Mom. When you die, you die.’”

The abuse didn’t stop with Kealiher’s death, and as the investigation stalled, the harassment against his mother began. Online, far-right extremists celebrated Kealiher’s killing, calling him a “terrorist,” a “piece of shit,” “scum,” she said. They tried to dox Kealiher’s sister, who is a teenager, and to find out where she went to school. The family never held a memorial for Kealiher because his relatives were too scared to attend, in case details of the service were revealed publicly. “It just terrified them,” said his mother. Even his old Taekwondo school was the target of social media venom.

The threats weren’t just online. Laura Kealiher said that right-wing activists urinated on a street memorial set up for her son and texted pictures of the “OK” hand gesture, a hate symbol, to a phone number that used to be his. Days after he was killed, a white truck with a Trump flag pulled up by her home, and two men got out, shouting insults, leaving only when she came out of the house with a weapon. Three months after Kealiher’s death, a group of far-right activists who had been behind some of the online abuse held a rally in downtown Portland. Kealiher’s mother showed up to confront them. A video recorded that day shows her getting into a physical altercation with a woman, knocking her to the ground and kicking her. “I’m not sorry,” she told me.

In a video, friends of Sean Kealiher mourn his death by lighting flares and candles, placing flowers, and tagging the Democratic Party of Oregon building near where he was killed in Portland, Ore., in October 2019.

More than a year after her son’s killing, Laura Kealiher is still looking for justice, although she is trying to reconcile her need for closure with the abolitionist politics he held so firmly. “Sean would not want the man in prison; he was against prisons,” she said. A survivor of abuse, she had a hard time accepting her son’s commitment to restorative justice and always felt that some people just belonged in prison. But that’s not what she wants for the man who killed him, she said: She just wants to sit down with him and hear his life story. “I just want him to say he’s sorry. I know that sounds crazy.” Kealiher credits her son for “radicalizing” her, she said, and noted that since his death, it has been anti-fascists and SHARPs who have protected and supported her where the justice system let her down.

While she does not believe they killed him, she has inherited her son’s hatred for the far-right, white supremacist extremists whom he had spent his life fighting and who have tormented her since his death. Most of all, she blames police, she said. “I want them accountable for not doing their job.”